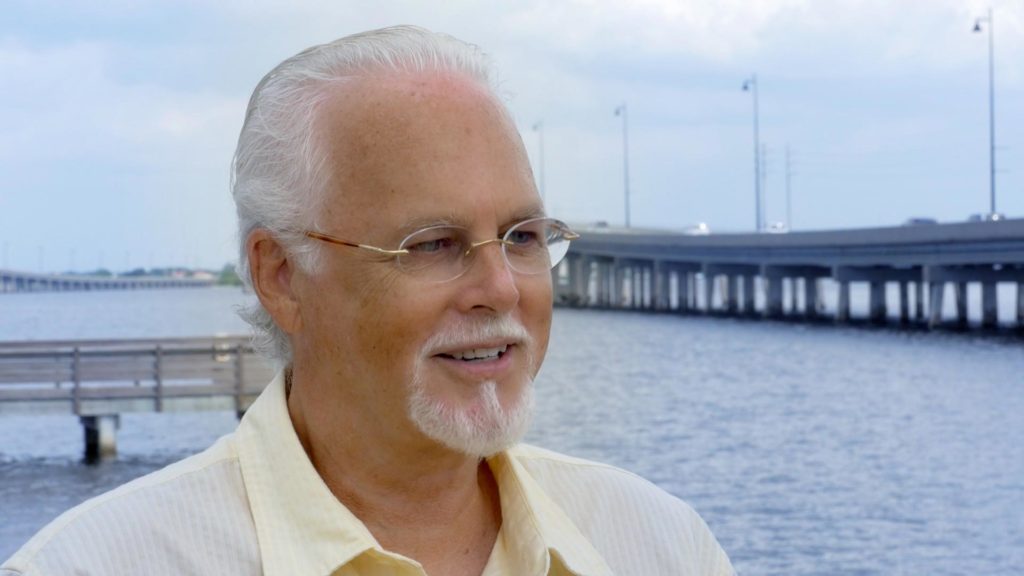

I bought William L (Bill) White’ book Pathways from the Culture of Addiction to the Culture of Recovery: A Travel Guide for Addiction Professionals many years ago. Bill is one of the most inspirational people I have come across in the recovery field, an opinion shared by many others. His book is a very important read, in particular in terms of helping one understand the nature of the culture of addiction and the culture of recovery, and how you can help people move from one culture to the other. It’s a book that is not just for addiction professionals; it is relevant to anyone who wishes to help people on a recovery journey from addiction.

Here is some essential reading which begins under the heading 8.4. Engaging the Client through Cultural and Personal Identification. (p. 190) [Of course, the person does not need to be a ‘client’, but someone who is being helped on their journey to recovery.]

‘Most clients entering a treatment environment / relationship do so with fear and ambivalence. The fear is the fear of an alien environment, the feeling of vulnerability and lack of control, and the suspicion that they are in a place where they will not be understood or accepted. The ambivalence embraces both the passionate desire to continue the drug relationship and the whimsical and desperate hope that something magical will occur and transform their lives.

The earliest moments in the initiation of the treatment relationship must communicate the following to the client:

- You are in the right place.

- You are with others like yourself.

- We understand you and the world you come from.

- We accept who you are and who you can become.

- This is the place where magic (change) can happen.

This period of initial contact can be designed to enhance the conclusions above through a process of both cultural and personal identification.’

Bill goes on to describe cultural and personal identification in detail. I just include a couple of paragraphs here [My bolds below]:

‘Cultural identification Is a process of shaping the treatment environment and staff-client communications in ways that reflect the client’s addictive experience. The attention to the environment and to early communications will enhance the clients’s identification and engagement with the treatment milieu.’ (p. 191)

‘Personal identification involves communicating positive regard and acceptance of what we see and what we don’t see in the client’s initial presentation of self in order to invite inclusion and relationship building. It involves acceptance of and sensitivity to the client’s ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, physical appearance, disabilities, and stage of life. By communicating such acceptance, we lower the client’s defence system and encourage the revelation of hidden aspects of self.’

Bill has written these words in relation to treatment, but they are of course relevant to recovery communities. In relation to this statement, I finish with these powerful words from Bill White which appeared at the end of his classic book Slaying the Dragon: The History of Addiction Treatment and Recovery in America:

‘During the past 150 years, “treatment” in the addictions field has been viewed as something that occurs within an institution – a medical, psychological, and spiritual sanctuary isolated from the community at large.

‘During the past 150 years, “treatment” in the addictions field has been viewed as something that occurs within an institution – a medical, psychological, and spiritual sanctuary isolated from the community at large.

In the future, this locus will be moved from the institution to the community itself. Treatment will be viewed as something that happens in indigenous networks of recovering people that exist within the broader community.

The shift will be from the emotional and cognitive processes of the client to the client’s relationship in a social environment. With this shift will come an expansion of the role of the clinician to encompass skills in community organization.

Such a transition does not deny the importance of the reconstruction of personal identity and other cognitive and emotional processes – or of the physical processes of healing – in addiction recovery. But it does recognize that such processes unfold within a social ecosystem and that this ecosystem, as much as the risk and resiliency in the individual, tips the scale towards recovery or continued self-destruction.

As these new community organizers extend their activities beyond the boundaries of traditional inpatient and outpatient treatment, they will need to be careful that they do not undermine the natural indigenous system of support that exist within the community.

The worst scenario would be that we would move into the lives of communities and – rather than help nurture the growth of indigenous supports – replace these natural, reciprocal relationships with ones that are professionalized, hierarchal, and commercialised.’

These words, were originally written in 1998, predict a future of developing recovery communities, which is occurring today. But Bill adds words of caution in his last sentence. These recovery developing communities should not become ‘professionalized, hierarchal, and commercialised.’